My grandparents on my mother's side were very interesting people. I figure now that I've gotten to the present day, I can now write about anything I want, so I'll write about my ancestry. I'm interested in how much of their traits continue on in me. This unlikely pairing of Ernestina Chacon, well-connected Spanish beauty, and Leo Rice, Welsh businessman, is a story that was repeated endlessly in the lives of many during the early twentieth century.

I spent a good bit of the day yesterday on the phone talking to my aunt, my mother's older sister who is almost 88 years old and gave me a lot of information about her parents. When Aunt Quetita laughs, she sounds like a girl. She is sharp as a tack, too. This is about her parents, my grandparents on my mother's side.

They met in a railroad station in Trinidad, Colorado. Ernestina's parents were part of the establishment in that town, and she was a good Catholic girl who had fallen in love with a soldier who was not Catholic. Over the period of two years, they met each other only three times before they were married. Since he was not Catholic, it was a bit of a scandal and the long-time priest at the church would not marry them. However, the parents were able to find another Catholic priest to bless the union, and the marriage of Mr. and Mrs. Leo Rice was launched.

Ernestina bore six children to Leo, starting with my uncle Anthony and then Quetita. Leo became a hotel manager and moved from place to place, trying to find a climate that would be healthy for his fragile firstborn son. My mother, Rita, the third child, was born in Springfield, Illinois. Eventually they moved to Southern California, where Ernestina had three more children: Edmund, Joseph, and finally Ernest. Six children in all, before Ernestina spoke with a doctor who told her how she could avoid having any more children. (She didn't know how come she kept getting pregnant, Quetita says.)

By this time, they had settled in Bakersfield, California. Leo was the manager of the Bakersfield Inn and eventually rented the attached drive-in restaurant. He managed the hotel and the very successful "Leo's Drive-In." It didn't hurt his profits that his wife was the cook for the entire restaurant, his two lovely (and buxom) daughters the carhops, and his sons all worked for next to nothing. Before long, they had moved to a large, two-story home.

My childhood memories of their beautiful house on V Street in Bakersfield (where we spent long periods when Daddy was gone TDY, temporary duty) included the most amazing grape arbor over the carport, which seemed to be always laden down with huge bunches of green seedless grapes. I would eat them until I was sick. The back yard continued a long way back, the first part a yard with fruit trees, Felix the duck who swam around in a large metal tub, and beyond that an overgrown rose garden, with fragrant roses assaulting my young nose. Funny how often smells bring back memories. I remember one time when I was actually living there long enough to attend school in Bakersfield.

As a child you live in your own world and don't really think about the adult world, or at least I didn't. I know that when my father was stationed outside of Fairfield, California, we spent a great deal of time in Bakersfield as well. That house is filled in my memories with many good times.

Leo developed diabetes and was very ill for many of the last years of his life, and he only lived to be 62. In my mind, though, he was extremely frail and old. My mother was very close to her father and suffered terribly when he died. I remember that she even had to go away for awhile, and as an adult I learned that she suffered a nervous breakdown during that time. There were three of us by then: me, my sister Norma Jean and little P.J. (Patricia June was always known by her initials as a baby.)

When Leo died, his wife of all those years learned that he was a gambler and had mortgaged that beautiful house to the hilt, without her knowledge. She was turned out of her home, and Grandma (I only called her that) never forgave Leo for what he had done. Years later when I was taking care of her in Santa Monica, after my bicycle trip across the country, I remember taking her to the cemetery where her son Joseph was buried. Leo was also buried there, and I asked her if she wanted to visit his grave too.

She stood beside me rapping the ground with her cane, looking straight ahead, before she answered me with an emphatic "No!" Even though it had been decades, she still would not forgive him. Grandma lived on for several more years, but she finally died at the age of 79, living many years longer than the doctors believed she would.

I learned from my grandmother that carrying grudges around can be very debilitating and harmful to the one carrying them. She had her children's and her grandchildren's lives to live, but I don't think she ever developed one for herself. It was very hard for me to leave Grandma after five months of caring for her, but I did, because I saw I would be swallowed up into her life and she would try to live hers through me.

This is the way it used to be for women, and I am also struck again by how much has changed in our culture during the past century. Ernestina was Mrs. Leo Rice, mother of six. I wonder who she would have been if the seed of her life had fallen into more fertile ground?

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Sunday, February 21, 2010

Choosing a new home

Last night I had a dream about my son Chris. Since it's been a while since I woke, I don't remember the particulars, but I know he was a teenager in my dream, and he was happy. Having spent so many years as a mom, I still feel like one. You can't stop being a parent just because your children have died before you.

In 2006, I had been working for almost three decades at NCAR, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and my duties for the past decade had taken me all over the world to arrange conferences and write reports after I returned to Boulder. This, plus my weekend activities at the Drop Zone, gave me a very full life. In fact, too full. I was getting tired as I approached my 64th birthday. Because I needed to reach Medicare age before I could retire, I was looking forward to turning 65.

Smart Guy and I began to think about our options. What did we want to do with our retirement years? He was already out of the work force and on Social Security, and I would be able to convert my TIAA/CREF annuities that I had been contributing to during my time at NCAR into a small monthly income. That, plus our two Social Security checks, would be what we would use to live on for the rest of our lives. That amount looked to be sufficient if we didn't have any huge expenses. It would not be enough to go on cruises and live extravagantly, but that isn't what we were looking for anyway.

In the summer of 2006, after having decided we wanted to live somewhere on the West Coast, we took a month-long car trip to Washington state. We looked at communities up and down the coast, and even gave a little thought to living across the border in Canada, but we found a small town situated 20 miles south of the Canadian border and 85 miles north of Seattle: Bellingham. The proximity to Vancouver and Seattle is important, but we didn't want to live in a big city. This town seemed to be the right size, a good jumping-off place.

The only real problem with the town, to me, is a major freeway passing north and south through the middle of town, I-5, which stretches from the Canadian border all the way to southern California. It gets a lot of traffic, and finding a place away from the white noise of traffic has been difficult. That aside, it has a great bus system, which is incredibly inexpensive for seniors ($35 for a three-month pass giving you unlimited rides throughout the entire county).

When we got back from our trip, I gave my boss a year's notice, telling him that I would be leaving at the end of March 2008. Hopefully I would be able to hire my replacement during that period. This also gave us enough time to figure out what we wanted to take and what to leave behind. Two paid-for Hondas would go with us, a little furniture, not much, and that was it.

In February 2008, Smart Guy set out with a few things packed into his Honda and drove to Bellingham. We talked on the phone daily, and we used our iChat feature on our laptops to video conference with each other, and he found a nice apartment within our price range and moved in on March 1, 2008. He lived there alone for a month while I finished up at NCAR, with a nice retirement party, and my boss Mickey gave me one at his house, where my women's group and private friends gathered to say goodbye to me. I did think I would return one day, but as of today I still haven't.

Smart Guy flew back to Boulder, we packed up my car and a medium-sized U-Haul truck, and I said goodbye to my chosen home of more than three decades, to find a new life in retirement. We had our cellphones, which worked well to talk to each other on the road and coordinate pit stops. On April 17, 2008, we drove up to our new place here in Bellingham, moved in our furniture, and started a new life.

What to do with myself? No job, no responsibilities, and no friends or family nearby. My own siblings all live in different places, but the majority of them live in Texas, which was never a place I wanted to retire in: too hot, too flat, and too conservative for this old hippie.

The first thing I did was join the YMCA. Bellingham has a great one, with exercise classes of all kinds every day, a sauna and steam bath for after the workout. I got a locker and moved in my exercise stuff, and started taking the bus to town each morning to attend a 9:00am class. Since the bus schedule brought me to town a little after 8:00am, I began hanging out at a local coffee shop for my morning latte. This is where the core of my new friends are: people who ride the bus with me every day, regulars at the gym, and regulars at the coffee shop. I also joined the Senior Center and began Thursday hikes with the Senior Trailblazers. I've been learning about the area through these hikes, and I've also made some great friends. In the summer we head to the high country, and in the winter we stay close to town. We head out, rain or shine.

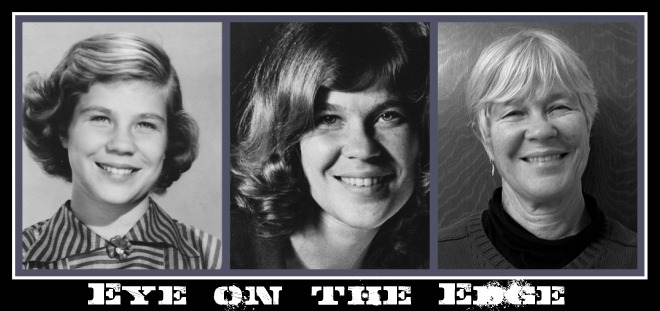

And almost exactly a year ago now, I started a blog. This activity has filled a great void in my life for creative writing. A few months ago I began this second blog, which I think of as the Eye blog (or in Mac speak, iBlog), giving me a place to write down and ruminate about how I got here, and where I want to go. I've written 15 posts to get to the present time, writing down the most difficult and wrenching events that have made me who I am today.

From here, I'm not sure where to go with this blog, but I suspect it will come to me before next Sunday. Writing in here in the early morning hours before I get out of bed has become a satisfying ritual. Once I've banged out the first draft, I re-read and edit it until I'm happy with it.

Then I hit "publish" and ponder what my life is all about.

In 2006, I had been working for almost three decades at NCAR, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and my duties for the past decade had taken me all over the world to arrange conferences and write reports after I returned to Boulder. This, plus my weekend activities at the Drop Zone, gave me a very full life. In fact, too full. I was getting tired as I approached my 64th birthday. Because I needed to reach Medicare age before I could retire, I was looking forward to turning 65.

Smart Guy and I began to think about our options. What did we want to do with our retirement years? He was already out of the work force and on Social Security, and I would be able to convert my TIAA/CREF annuities that I had been contributing to during my time at NCAR into a small monthly income. That, plus our two Social Security checks, would be what we would use to live on for the rest of our lives. That amount looked to be sufficient if we didn't have any huge expenses. It would not be enough to go on cruises and live extravagantly, but that isn't what we were looking for anyway.

In the summer of 2006, after having decided we wanted to live somewhere on the West Coast, we took a month-long car trip to Washington state. We looked at communities up and down the coast, and even gave a little thought to living across the border in Canada, but we found a small town situated 20 miles south of the Canadian border and 85 miles north of Seattle: Bellingham. The proximity to Vancouver and Seattle is important, but we didn't want to live in a big city. This town seemed to be the right size, a good jumping-off place.

The only real problem with the town, to me, is a major freeway passing north and south through the middle of town, I-5, which stretches from the Canadian border all the way to southern California. It gets a lot of traffic, and finding a place away from the white noise of traffic has been difficult. That aside, it has a great bus system, which is incredibly inexpensive for seniors ($35 for a three-month pass giving you unlimited rides throughout the entire county).

When we got back from our trip, I gave my boss a year's notice, telling him that I would be leaving at the end of March 2008. Hopefully I would be able to hire my replacement during that period. This also gave us enough time to figure out what we wanted to take and what to leave behind. Two paid-for Hondas would go with us, a little furniture, not much, and that was it.

In February 2008, Smart Guy set out with a few things packed into his Honda and drove to Bellingham. We talked on the phone daily, and we used our iChat feature on our laptops to video conference with each other, and he found a nice apartment within our price range and moved in on March 1, 2008. He lived there alone for a month while I finished up at NCAR, with a nice retirement party, and my boss Mickey gave me one at his house, where my women's group and private friends gathered to say goodbye to me. I did think I would return one day, but as of today I still haven't.

Smart Guy flew back to Boulder, we packed up my car and a medium-sized U-Haul truck, and I said goodbye to my chosen home of more than three decades, to find a new life in retirement. We had our cellphones, which worked well to talk to each other on the road and coordinate pit stops. On April 17, 2008, we drove up to our new place here in Bellingham, moved in our furniture, and started a new life.

What to do with myself? No job, no responsibilities, and no friends or family nearby. My own siblings all live in different places, but the majority of them live in Texas, which was never a place I wanted to retire in: too hot, too flat, and too conservative for this old hippie.

The first thing I did was join the YMCA. Bellingham has a great one, with exercise classes of all kinds every day, a sauna and steam bath for after the workout. I got a locker and moved in my exercise stuff, and started taking the bus to town each morning to attend a 9:00am class. Since the bus schedule brought me to town a little after 8:00am, I began hanging out at a local coffee shop for my morning latte. This is where the core of my new friends are: people who ride the bus with me every day, regulars at the gym, and regulars at the coffee shop. I also joined the Senior Center and began Thursday hikes with the Senior Trailblazers. I've been learning about the area through these hikes, and I've also made some great friends. In the summer we head to the high country, and in the winter we stay close to town. We head out, rain or shine.

And almost exactly a year ago now, I started a blog. This activity has filled a great void in my life for creative writing. A few months ago I began this second blog, which I think of as the Eye blog (or in Mac speak, iBlog), giving me a place to write down and ruminate about how I got here, and where I want to go. I've written 15 posts to get to the present time, writing down the most difficult and wrenching events that have made me who I am today.

From here, I'm not sure where to go with this blog, but I suspect it will come to me before next Sunday. Writing in here in the early morning hours before I get out of bed has become a satisfying ritual. Once I've banged out the first draft, I re-read and edit it until I'm happy with it.

Then I hit "publish" and ponder what my life is all about.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Till we meet again

Yes, this post is hard to write, but not as bad as if it were still September 2002. That's when I wrote a remembrance to my son Chris at work. He died of what is called "sudden cardiac death" while jogging. Since this happened, I have seen several young people, usually men, written up on the obituary page as having died of the same thing. Part of the difficulty of it is that there is no warning, either for them, or for their loved ones.

I had just returned from Quincy where I had a two-week vacation, if you can call it that, jumping out of airplanes at the World Freefall Convention, tanned and happy to be back at work. I remember the phone ringing at 9:00am in the office and hearing the clicks and pops of a long-distance connection, and then a hysterical woman on the other end, saying things I could not understand. (Chris' wife Silvia was German and didn't speak great English at the best of times.) When I finally put together who she was, I felt a sick feeling and asked her what was wrong. She babbled something about Chris and finally said, "he's dead!" It was like being kicked in the stomach.

Finally Chris' Commanding Officer came on the phone and told me that Chris had died while he was on a three-month tour of duty in Macedonia. He told me in the gentlest way that I was to go home and wait for the soldiers to come to my house and inform me. I have a memory of one of my co-workers driving me home, but I was in shock. Once I got home, three young uniformed soldiers knocked on my door, one of them a young woman holding flowers in her hands and looking scared. They answered my questions, and told me that Chris' wife had asked for him to be buried in Germany, and as the next of kin, she could make that decision.

Then I found that there was no provision from the Army for me to get to Germany to see my son one more time. You see, I was no longer considered the next of kin, Silvia was. But when my boss Mickey heard about this, he presented me with a round-trip ticket to Frankfurt and $500 and told me to just go. I went to Germany. The link above will tell you about my time there. I learned that Chris had been happy and very well liked, and I spoke to his unit one morning about how glad I was that he had found his place in life.

The funeral was very tough. Nobody had told me about the Army's calling his name three times as if he were to answer, and when he didn't, they played "taps" to honor the fallen soldier. It was truly hard to bear. Some very thoughtful person had recorded it and gave me a copy of the Memorial Service. I have never watched it, but it holds a very special place on my keepsake shelf, along with the triangular box that holds the flag with three spent shells inside.

I was 59 years old when Chris died on August 15, 2002, on the anniversary of the day that his brother Stephen had been born 36 years earlier. The difference between me, the 59-year-old, and that young 22-year-old who lost her child was like night and day. If anyone were to ask me which one was harder to bear, there is no question: the poor young woman who lost her son who never had a chance to live, or the older woman who lost her other son after he had found himself, a career and a wife -- I don't have to tell you, you already know.

I also wrote another post about my two lost sons on my other blog, which I called "Amethyst Remembrance" after a favorite Emily Dickinson poem. It gives more detail, but here I want to talk about who I am today, and how the loss of my children has helped to make me who I am. When Stephen died, I could not bear to be in the same room with a small baby, whose beautiful chubby cheeks or fat arms tore at my heart and made me so aware of my loss. I turned away and avoided touching that place inside that felt like it would never be healed. Chris suffered too, because he reminded me of his brother, and I wouldn't let myself love him unconditionally. I hardened myself in ways I didn't even realize. I think this is one reason why I went from one husband to another: it was impossible for me to reach down inside and be truly authentic with anybody.

But when Chris died, I had found a job, a life I loved, and a man who supported me emotionally. He had helped me work through some of the buried grief and I learned that I was not going to find myself through another person, but through examining my own motives and desires. This is much easier to do when you have a partner who knows how to facilitate this, and I have been very fortunate to have Smart Guy, who always asked the right questions.

Because I had healed from my earlier wounds, I was able to grieve properly for Chris. I didn't look away when I went to Germany and met his fellow soldiers, when I went to the PT field and did pushups and jumping jacks in his place. I let it in. And although I miss calling him and hearing from him on Mother's Day and his birthday (he called me then, not on mine), I know that he had found himself before he died. It's all any mother can ask for.

Chris died just before the war in Iraq started. Every one of those young men I met in Germany was deployed to Iraq, and Chris would certainly have gone there too, and would probably have died there instead of in Macedonia. He never had to go to war, and for that I am grateful. His roommate in Macedonia told me how Chris would come back to their room after having been in the heat of the day, guarding the border: he would strip down to his shorts, turn the air conditioning to high, grab a beer out of the fridge, and plop down with a satisfying "ahhhhh!" That's the way I like to think of him, with a hedonistic grin and pleased with a job well done.

When you don't have grandchildren, and both of your offspring are gone from the world, your life doesn't necessarily include small children any more. But I find myself enjoying them so very much. There is a young boy, 13 months old, whose dad brings him every morning to the coffee shop where I have my latte. I've watched him over the past few months learn to walk, first by holding onto tables, then those first tentative steps like a drunken sailor, and now the confidence that he doesn't have to hold onto anything. It gives me such pleasure to watch, knowing that this beautiful child doesn't have to be my kin for me to love him.

Next Sunday I'll talk about these last few years that took me away from a job I had for almost three decades, and how I moved from a full-time job into retirement.

I had just returned from Quincy where I had a two-week vacation, if you can call it that, jumping out of airplanes at the World Freefall Convention, tanned and happy to be back at work. I remember the phone ringing at 9:00am in the office and hearing the clicks and pops of a long-distance connection, and then a hysterical woman on the other end, saying things I could not understand. (Chris' wife Silvia was German and didn't speak great English at the best of times.) When I finally put together who she was, I felt a sick feeling and asked her what was wrong. She babbled something about Chris and finally said, "he's dead!" It was like being kicked in the stomach.

Finally Chris' Commanding Officer came on the phone and told me that Chris had died while he was on a three-month tour of duty in Macedonia. He told me in the gentlest way that I was to go home and wait for the soldiers to come to my house and inform me. I have a memory of one of my co-workers driving me home, but I was in shock. Once I got home, three young uniformed soldiers knocked on my door, one of them a young woman holding flowers in her hands and looking scared. They answered my questions, and told me that Chris' wife had asked for him to be buried in Germany, and as the next of kin, she could make that decision.

Then I found that there was no provision from the Army for me to get to Germany to see my son one more time. You see, I was no longer considered the next of kin, Silvia was. But when my boss Mickey heard about this, he presented me with a round-trip ticket to Frankfurt and $500 and told me to just go. I went to Germany. The link above will tell you about my time there. I learned that Chris had been happy and very well liked, and I spoke to his unit one morning about how glad I was that he had found his place in life.

The funeral was very tough. Nobody had told me about the Army's calling his name three times as if he were to answer, and when he didn't, they played "taps" to honor the fallen soldier. It was truly hard to bear. Some very thoughtful person had recorded it and gave me a copy of the Memorial Service. I have never watched it, but it holds a very special place on my keepsake shelf, along with the triangular box that holds the flag with three spent shells inside.

I was 59 years old when Chris died on August 15, 2002, on the anniversary of the day that his brother Stephen had been born 36 years earlier. The difference between me, the 59-year-old, and that young 22-year-old who lost her child was like night and day. If anyone were to ask me which one was harder to bear, there is no question: the poor young woman who lost her son who never had a chance to live, or the older woman who lost her other son after he had found himself, a career and a wife -- I don't have to tell you, you already know.

I also wrote another post about my two lost sons on my other blog, which I called "Amethyst Remembrance" after a favorite Emily Dickinson poem. It gives more detail, but here I want to talk about who I am today, and how the loss of my children has helped to make me who I am. When Stephen died, I could not bear to be in the same room with a small baby, whose beautiful chubby cheeks or fat arms tore at my heart and made me so aware of my loss. I turned away and avoided touching that place inside that felt like it would never be healed. Chris suffered too, because he reminded me of his brother, and I wouldn't let myself love him unconditionally. I hardened myself in ways I didn't even realize. I think this is one reason why I went from one husband to another: it was impossible for me to reach down inside and be truly authentic with anybody.

But when Chris died, I had found a job, a life I loved, and a man who supported me emotionally. He had helped me work through some of the buried grief and I learned that I was not going to find myself through another person, but through examining my own motives and desires. This is much easier to do when you have a partner who knows how to facilitate this, and I have been very fortunate to have Smart Guy, who always asked the right questions.

Because I had healed from my earlier wounds, I was able to grieve properly for Chris. I didn't look away when I went to Germany and met his fellow soldiers, when I went to the PT field and did pushups and jumping jacks in his place. I let it in. And although I miss calling him and hearing from him on Mother's Day and his birthday (he called me then, not on mine), I know that he had found himself before he died. It's all any mother can ask for.

Chris died just before the war in Iraq started. Every one of those young men I met in Germany was deployed to Iraq, and Chris would certainly have gone there too, and would probably have died there instead of in Macedonia. He never had to go to war, and for that I am grateful. His roommate in Macedonia told me how Chris would come back to their room after having been in the heat of the day, guarding the border: he would strip down to his shorts, turn the air conditioning to high, grab a beer out of the fridge, and plop down with a satisfying "ahhhhh!" That's the way I like to think of him, with a hedonistic grin and pleased with a job well done.

When you don't have grandchildren, and both of your offspring are gone from the world, your life doesn't necessarily include small children any more. But I find myself enjoying them so very much. There is a young boy, 13 months old, whose dad brings him every morning to the coffee shop where I have my latte. I've watched him over the past few months learn to walk, first by holding onto tables, then those first tentative steps like a drunken sailor, and now the confidence that he doesn't have to hold onto anything. It gives me such pleasure to watch, knowing that this beautiful child doesn't have to be my kin for me to love him.

Next Sunday I'll talk about these last few years that took me away from a job I had for almost three decades, and how I moved from a full-time job into retirement.

Sunday, February 7, 2010

Intensity on many levels

Sunday morning again. I just finished re-reading last week's post to make sure I don't miss anything. When we got married in freefall, I was 51 years old and a veteran of three previous marriages that didn't work out. For two decades, I was sure that I would never marry again, but when we did, finding our way forward centered on our shared love of skydiving. He started skydiving in 1962 and was well known in the small skydiving world of the 1960s and 1970s, and I made my first jump in 1990, so we were at opposite ends of learning about skydiving.

To someone who doesn't skydive, it might seem a little odd to say that it is a learning experience that continues as long as you are jumping. And I didn't know what I wanted to do with my jumping life. You see, there are different disciplines in skydiving: relative work (RW), freestyle (back then anyway), canopy formations (made after you open your parachute), videography, and a few others. I decided I wanted to become an instructor, which is probably the hardest and most difficult experience I've ever had. Smart Guy would pretend to be a student for me, and I would try to give him signals in freefall and control his antics as if he were a student.

After I had almost 1,000 jumps, I thought I was ready to attend a course. These courses are held at various places around the country several times a year. We went to Davis, California, and I entered the stress of two days of classroom, then a week of being tested in the air by having an evaluator pretending to be a student, with video (taken by a third person). You paid lots of money for this privilege, plus the slots on the plane for three people.

I failed miserably. I did not even get close to passing the course my first time through. After going home and spending every waking moment talking with Smart Guy about what I needed to learn and practicing every weekend, I went off to Texas in 1994 to try again. It was just a month after we got married that I went there. And I passed! On June 18, 1994, I became an AFF (Accelerated Freefall) skydiving instructor! And the learning went on and on, with me loving it and learning how to help others to become a skydiver.

Every August, we went off to the World Freefall Convention in Quincy, Illinois, and we had been given a big area to set up for young (meaning not many jumps) skydivers to hang out in. This would keep them safer and still learning instead of getting in over their heads. I didn't particularly want to perform complicated skydives with people, and I was so very happy to make up simple jumps and had as many as a dozen other skydivers working for me, doing the same thing. Smart Guy and I ran this tent for inexperienced jumpers for many years. By the year 2000, I had accumulated over 2,000 skydives.

By this time, every weekend I was instructing, and my job became more intense. I was promoted to a salaried position in 1999, and I began to travel with my boss all over the world. My first trip was to Geneva, then Macao in 2000, and I ended up making many international trips to interesting places. I organized several dozen international scientific meetings and helped to write the report that followed.

As you can imagine, my life was very full. I never spent a day doing anything but going either to work, international travel, teaching skydiving on the weekends, or going off to skydiving events. And then, a mistake under canopy. A bad one.

On June 18, 2000, I was trying to land my parachute in high winds and made a turn close to the ground, which ended up with me fracturing my pelvis in six places, shattering the sacrum on the right side. I wrote about the experience on my other blog here. All the gory details are on that other post, but here I want to talk about what the accident did to our relationship. It only deepened our commitment to one another. I was completely and utterly dependent on Smart Guy for everything, from cooking for me, emptying the commode, helping me get around. It was hard on him, I know, but he never complained and kept his usual humor.

When I was finally able to get around by myself again and the external fixator had been removed from my pelvis, I returned to work after missing a couple of months. My job was waiting for me, and I was able to return to the skydiving world over Christmas vacation in 2000, at Eloy, Arizona, while attending Skydive Arizona's annual Christmas event. Six months later, I was back in the air!

Before too many months, I was back teaching students again, and I also spent many a Saturday teaching the First Jump Course, teaching as many as a dozen students to make their first jump safely. I got so involved in all this that I decided to run for Regional Director for the United States Parachute Association, so that I could be involved in helping with skydiving safety and training issues. I was on the Board for four years, and I finally learned that I am not a political person. And that is what it was: you had to learn how to get the votes on the Board in order to get anything passed. I made a lot of friends in the national skydiving arena, but I was not cut out to be a Board member.

So, as you can see, skydiving and my job were very intense, and our relationship shined right through all this. But I began to change. As Smart Guy once said to me, you can't have a hundred jumps forever; the experience of skydiving changes as you move through it, and after a while I no longer felt it was necessary for me to be at the Drop Zone EVERY weekend, or pushing myself to the limit every moment of every day.

In August 2002, another part of my life changed when my son Chris died suddenly. His wife called me from Germany and I learned that he was gone. I'll tell you about that tragic time in my life next week.

To someone who doesn't skydive, it might seem a little odd to say that it is a learning experience that continues as long as you are jumping. And I didn't know what I wanted to do with my jumping life. You see, there are different disciplines in skydiving: relative work (RW), freestyle (back then anyway), canopy formations (made after you open your parachute), videography, and a few others. I decided I wanted to become an instructor, which is probably the hardest and most difficult experience I've ever had. Smart Guy would pretend to be a student for me, and I would try to give him signals in freefall and control his antics as if he were a student.

After I had almost 1,000 jumps, I thought I was ready to attend a course. These courses are held at various places around the country several times a year. We went to Davis, California, and I entered the stress of two days of classroom, then a week of being tested in the air by having an evaluator pretending to be a student, with video (taken by a third person). You paid lots of money for this privilege, plus the slots on the plane for three people.

I failed miserably. I did not even get close to passing the course my first time through. After going home and spending every waking moment talking with Smart Guy about what I needed to learn and practicing every weekend, I went off to Texas in 1994 to try again. It was just a month after we got married that I went there. And I passed! On June 18, 1994, I became an AFF (Accelerated Freefall) skydiving instructor! And the learning went on and on, with me loving it and learning how to help others to become a skydiver.

Every August, we went off to the World Freefall Convention in Quincy, Illinois, and we had been given a big area to set up for young (meaning not many jumps) skydivers to hang out in. This would keep them safer and still learning instead of getting in over their heads. I didn't particularly want to perform complicated skydives with people, and I was so very happy to make up simple jumps and had as many as a dozen other skydivers working for me, doing the same thing. Smart Guy and I ran this tent for inexperienced jumpers for many years. By the year 2000, I had accumulated over 2,000 skydives.

By this time, every weekend I was instructing, and my job became more intense. I was promoted to a salaried position in 1999, and I began to travel with my boss all over the world. My first trip was to Geneva, then Macao in 2000, and I ended up making many international trips to interesting places. I organized several dozen international scientific meetings and helped to write the report that followed.

As you can imagine, my life was very full. I never spent a day doing anything but going either to work, international travel, teaching skydiving on the weekends, or going off to skydiving events. And then, a mistake under canopy. A bad one.

On June 18, 2000, I was trying to land my parachute in high winds and made a turn close to the ground, which ended up with me fracturing my pelvis in six places, shattering the sacrum on the right side. I wrote about the experience on my other blog here. All the gory details are on that other post, but here I want to talk about what the accident did to our relationship. It only deepened our commitment to one another. I was completely and utterly dependent on Smart Guy for everything, from cooking for me, emptying the commode, helping me get around. It was hard on him, I know, but he never complained and kept his usual humor.

When I was finally able to get around by myself again and the external fixator had been removed from my pelvis, I returned to work after missing a couple of months. My job was waiting for me, and I was able to return to the skydiving world over Christmas vacation in 2000, at Eloy, Arizona, while attending Skydive Arizona's annual Christmas event. Six months later, I was back in the air!

Before too many months, I was back teaching students again, and I also spent many a Saturday teaching the First Jump Course, teaching as many as a dozen students to make their first jump safely. I got so involved in all this that I decided to run for Regional Director for the United States Parachute Association, so that I could be involved in helping with skydiving safety and training issues. I was on the Board for four years, and I finally learned that I am not a political person. And that is what it was: you had to learn how to get the votes on the Board in order to get anything passed. I made a lot of friends in the national skydiving arena, but I was not cut out to be a Board member.

So, as you can see, skydiving and my job were very intense, and our relationship shined right through all this. But I began to change. As Smart Guy once said to me, you can't have a hundred jumps forever; the experience of skydiving changes as you move through it, and after a while I no longer felt it was necessary for me to be at the Drop Zone EVERY weekend, or pushing myself to the limit every moment of every day.

In August 2002, another part of my life changed when my son Chris died suddenly. His wife called me from Germany and I learned that he was gone. I'll tell you about that tragic time in my life next week.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)