|

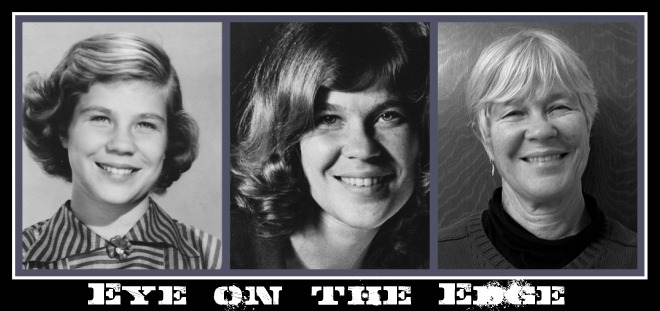

| Norma Jean (then and now), Allison, Lexie, me |

I woke several times during the night wondering what I would post about this morning, thinking of how the "Sunday morning meditation" has morphed into a Sunday morning obligation. I set these things up for myself. Somehow I am a happier person when I have deadlines to meet. Probably I developed that set of muscles during my working years, I don't know, but it's definitely a part of me now. It's just after 5:00am, hot tea beside me, my partner sleeping; the birds are singing outside the window and a rooster is crowing in the distance. The stage is set, and now I write.

My father wanted a boy when I was growing up. Although he had three girls, he still wished for a boy, and when I was sixteen, my brother was born. His birth was followed in quick succession by three more babies, one a year. All girls. My youngest sister is almost exactly twenty years younger than me, and she and I will both have "big" birthdays this fall: she turns fifty, and I turn seventy. Mama was 39 when Fia was born, and 19 when she had me.

I don't know exactly why it was so important for Daddy to have a boy, being a girl and obviously a disappointment to him, I didn't even question it back then. It's very different these days. I myself had two sons, and I wished for a daughter because I knew girls much better than I knew boys, but I loved both my sons, even if I didn't get to dress them in frills and dresses. Was it to carry on the family name? Well, in that case, Daddy was a complete success, because we are all Stewarts in this picture: Norma Jean and her husband Pete changed their name legally to Stewart, as Pete's name (Polish) was constantly being mangled. Once they decided to do it, both of their children also became Stewarts. It's hard for me to even think of them as being other than Stewarts. When Pete died, the paperwork with the name change came up, and I saw the problem: it was misspelled in the process and caused some delays in getting everything legally transferred to Norma Jean.

Allison and Peter, their children, are Stewarts. I changed my name back to Stewart after years of taking on other men's names in marriages that failed. When Smart Guy and I married at fifty, there was simply no question of whether I would take his name. Why in the world would I? We would have no children, we were both established in our lives with the names we had. The world had moved on since the sixties, and many women don't change their names when they marry, and many couples don't even bother with the legalities at all and stay together but single.

Allison is a Lt. Colonel in the Army, a career woman who is not married, and she realized that if she was going to have a child, it would need to be soon. She decided to go the IVF route, using donor sperm, and little Lexie is the result. Today she is a beautiful little toddler, the apple of her mother's eye, and she will be raised without any father at all. She is very social and enjoys her days at the Day Care Center where she has become everyone's favorite. Lexie is also a Stewart. She has begun to develop a look that is all her own, but since we know little about one side of her genetic makeup, I wonder if she favors him at all. I know that Allison is very smart and has a gift for mathematics, and she chose a donor who also has math capabilities. Lexie is likely to have that trait as well.

A few years ago, CBS featured a program about sperm donor siblings and the new kinds of family ties that have formed because of people wanting to know about other relatives. Allison arranged to give Lexie the opportunity, when she comes of age, to find out about the donor. It is amazing to me to learn that more than 30,000 children are born in the United States every year from anonymous donor sperm. Yes, life has definitely changed in the years since Daddy was wishing for a boy to carry on his family name.

Life throws a curve ball every now and then. Because both of my sons died, I will not be carrying on the family name myself, but my sister, whose husband took her name, has two children who do. And the one female in the equation had a child who carries the Stewart name. Even though I have no living children, I have a very large family, with five siblings who all have children, and some of those children are busy having offspring of their own. Mama and Daddy would be proud.

It's time to post this and start the rest of my day. It has been very wet; yesterday it poured, raining much harder than I am accustomed to in this part of the country. I checked the garden, everything survived the onslaught, but I am still hoping for a break in the weather so I can get in a few jumps. It's now been three weeks since I was last able to make a skydive. I'll check the weather and if there is any chance at all, I'll head south to Snohomish to play in the air.