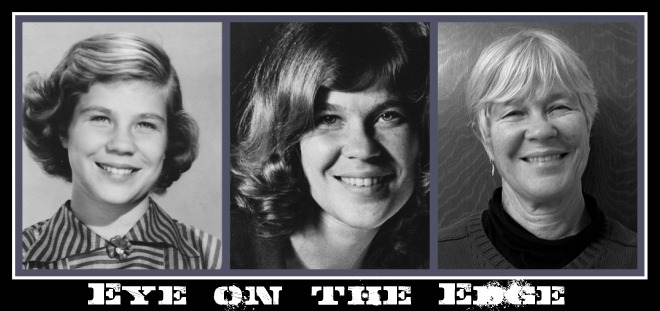

This picture of me, taken last week by Fred while we were on our hike to Goat Lake, shows a nice smiling lady standing in front of a beautiful scene. But something about the lovely picture nagged at me and I just couldn't figure it out at first. Then it hit me: I am getting older, and no matter how much I exercise and diet, time doesn't stand still for anybody, and it shows. The three pictures I keep in the header of this blog show a progression of aging, and it hasn't stopped or slowed down at all. This is natural and inevitable, but every once in a while, I notice and think about where I'm headed.

The world has changed so much since I was born almost seven decades ago. Even though birth and death are major events to an individual, they continue to occur all over the world at every moment, not just with humanity but with everything. It's usually so gradual that we don't notice, but if I think of the world as it was when I was young and compare it to the world I live in today, the differences are staggering. The population of the United States has more than doubled. How could that not be noticeable? But it also has happened gradually and although I realize how many more people are around, I always think that it is simply where I am living, and that somewhere the world exists as it did when I was little. But it's just not true. It's gone. The Wizard of Oz was made in 1939, and we still watch it occasionally on TV. Every single person, from stage hand to Munchkin to actor, has died. There was no massive catastrophe that caused this, just the simple passage of time.

The world doesn't stand still for anybody or anything. The wrinkled and spotted hands that type this today were once pretty, with manicured and painted nails, and I cared a great deal how they looked. That has also gone; today they function just fine, and I cannot imagine putting polish on my nails ever again. It just doesn't have the importance it once did. But today I notice, marking another change that happened while I wasn't paying attention.

If I could see a map of the United States with a light winking on at every birth, and a light winking off at every death, I might notice an upward trend. More people are being born than are dying in this part of the world, and this not only changes the quality of each life, but the sheer numbers cause me to realize that it cannot continue at this rate for much longer. There are more than 312 million of us in the US today, and when I was born, it was around 140 million. And even though I'm old now, it's taken less than seventy years for this enormous change to occur. The demographics are fascinating to me, and if you are interested, take a look for yourself. This is just in my small corner of the world; it's happening everywhere. I remember when I was in school learning about the fact that the world population would reach 6 billion by the turn of the century. At the time, this represented a doubling of the 3 billion on the planet. I couldn't even begin to imagine how different life would be, but the gradual rate of change has made it noticeable but not incredibly so. Certainly nothing like I imagined.

The other side of the passage of time has been the incredible rate of change in connectivity. I'm sitting here with a laptop that is connected to the world in ways that I could never have imagined even a decade ago. Yesterday I video chatted with my sister on Skype; this morning I've googled several items to check facts or download a picture, and I am writing this article on a blog that will appear on your own computer instantly after I hit "publish." If you try to imagine how that sentence would have puzzled someone who tried to make sense of it just a few short years ago: what's a Google? Skype? Blog?

It all seems so natural to me. I can hardly imagine how different my life would be without my connections. Smart Guy and I each have a cellphone and can talk to each other while out walking or while driving somewhere (although here in Washington state, I now pull over if the phone rings so I don't get a ticket). But how cool is that? And the best part is that I can TURN IT OFF if I feel like it. I remember how annoyed I would get when I would receive a phone call when I wasn't feeling receptive. All these changes have come in the past few years, too. We don't even have a landline any more.

Thinking about the passage of time, of the inevitability of change, I feel a little like I'm standing on the edge of a cliff looking down into a beautiful valley. I realize that as I can see everything from this vantage point, I can also feel the breeze lifting my hair and the rush of exhilaration that comes from having climbed this high.

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Whatever comes

I took this picture last Thursday while we Trailblazers were on our hike up Welcome Pass, which I wrote about on my other blog here. It was a beautiful day and a very hard hike; my legs have still not recovered and it's Sunday morning already. But it was totally worth it for the views and the wildflowers.

Last night I tossed and turned and wondered what I would write about this morning. The past few posts have been on the painful side, and the only thing I really hope turns out from this stream of consciousness attempt (hence the title "whatever comes") is that is be uplifting. I'm weary of looking at the past and wondering how I got here. Where is "here," anyway?

I'm reading an interesting book by Henry Alford, "How to Live: A Search for Wisdom from Old People." The inside cover has teasers like "Part family memoir, part Studs Terkel, How to Live is more than just a compendium of sage advice; it is a celebration of living well." So far (I'm on page 61), I'd say that is pretty accurate. Lots of food for thought. Maybe that's one reason why I'm feeling introspective without old memories crowding into my brain.

Alford peered into the philosophies of some old sages: Confucius (551 B.C.—479 B.C.), Buddha (563 B.C.—483 B.C.), and Socrates (470 B.C.—399 B.C.). For some reason I noticed that all three of these sages were right around 70 years old when they died, and I'm getting right up there with what has for so long been considered a full, complete life. What wisdom have I come up with? Not that I put myself into the same category as these old sages, but heck, who's to say I can't come up with some modern equivalent? For one thing, we in the modern age have unprecedented access to so much information, not to mention a new paradigm for communication: the blogosphere, which allows me to ruminate and share my thoughts, with instant feedback and unlimited possibilities. I have at this moment 78 followers, which means, if we were in a room together, it would have to be a big one. I picture the virtual classroom where we are gathered, with ideas and warm sentiments being shared. Lots of virtual hugs, too. This scene makes me smile just to think of it.

Last night I went to see "The Help," a movie adapted from a novel I read recently. Scenes from that movie kept coming up to me during my nighttime tossing. Viola Davis is magnificent as Aibileen, one of the main characters. The film adaptation is every bit as good as the book, to me, but something about the movie kept nagging at me. The theater was crowded, and people laughed and applauded at parts they liked, which always changes my experience, causing me to get caught up in the shared experience. After reading the reviews, I was able to put my finger on the same nagging discomfort that I felt from the book as well: somehow the interpretation of black maids in 1960s-era Jackson, Mississippi, flattened the historical era into larger-than-life villains and heroines. I lived through that time, too; it was a time like no other, but it was very complex. This is not to say I didn't like the book or the movie. Both were very worthwhile, and I wonder what other people think.

After all, I'm here in this new era: the crowded room where we share with one another gives me access to the wisdom and insight of all of you. I'm sitting here in the still-dark morning, laptop and cup of tea at hand, thinking large thoughts and smiling to myself. Today I'll get up and head down to Snohomish to jump out of airplanes with my friends (hopefully), come home tired and renewed, and check my email to find out how this stream of consciousness blog went over with you.

Last night I tossed and turned and wondered what I would write about this morning. The past few posts have been on the painful side, and the only thing I really hope turns out from this stream of consciousness attempt (hence the title "whatever comes") is that is be uplifting. I'm weary of looking at the past and wondering how I got here. Where is "here," anyway?

I'm reading an interesting book by Henry Alford, "How to Live: A Search for Wisdom from Old People." The inside cover has teasers like "Part family memoir, part Studs Terkel, How to Live is more than just a compendium of sage advice; it is a celebration of living well." So far (I'm on page 61), I'd say that is pretty accurate. Lots of food for thought. Maybe that's one reason why I'm feeling introspective without old memories crowding into my brain.

Alford peered into the philosophies of some old sages: Confucius (551 B.C.—479 B.C.), Buddha (563 B.C.—483 B.C.), and Socrates (470 B.C.—399 B.C.). For some reason I noticed that all three of these sages were right around 70 years old when they died, and I'm getting right up there with what has for so long been considered a full, complete life. What wisdom have I come up with? Not that I put myself into the same category as these old sages, but heck, who's to say I can't come up with some modern equivalent? For one thing, we in the modern age have unprecedented access to so much information, not to mention a new paradigm for communication: the blogosphere, which allows me to ruminate and share my thoughts, with instant feedback and unlimited possibilities. I have at this moment 78 followers, which means, if we were in a room together, it would have to be a big one. I picture the virtual classroom where we are gathered, with ideas and warm sentiments being shared. Lots of virtual hugs, too. This scene makes me smile just to think of it.

Last night I went to see "The Help," a movie adapted from a novel I read recently. Scenes from that movie kept coming up to me during my nighttime tossing. Viola Davis is magnificent as Aibileen, one of the main characters. The film adaptation is every bit as good as the book, to me, but something about the movie kept nagging at me. The theater was crowded, and people laughed and applauded at parts they liked, which always changes my experience, causing me to get caught up in the shared experience. After reading the reviews, I was able to put my finger on the same nagging discomfort that I felt from the book as well: somehow the interpretation of black maids in 1960s-era Jackson, Mississippi, flattened the historical era into larger-than-life villains and heroines. I lived through that time, too; it was a time like no other, but it was very complex. This is not to say I didn't like the book or the movie. Both were very worthwhile, and I wonder what other people think.

After all, I'm here in this new era: the crowded room where we share with one another gives me access to the wisdom and insight of all of you. I'm sitting here in the still-dark morning, laptop and cup of tea at hand, thinking large thoughts and smiling to myself. Today I'll get up and head down to Snohomish to jump out of airplanes with my friends (hopefully), come home tired and renewed, and check my email to find out how this stream of consciousness blog went over with you.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Anniversaries

Tomorrow is the ninth anniversary of my son Chris' death. August 15 is also the day in 1964 when my second son, Stephen, was born. Time has a way of helping one to forget the joy and pain we experienced in the past. Sometimes nine years seems a long time ago, and sometimes it seems much more recent. The remains of both of my sons lie in separate graves somewhere, but I wouldn't visit them, even if I could. Stephen in Flint, Michigan, and Chris in Bamberg, Germany. To me, graveyards don't contain the important part of a person's remains.

Somebody else made the decision in each case to bury them. I myself will have my body cremated and leave nothing but ashes behind, hopefully to be scattered in some beautiful place. But it won't matter much to me in any event. It's those of us left behind that it matters to. Silvia, Chris' wife, wanted him buried in her cemetery so she could visit him, and that's fine. Everyone has different ways to commemorate those who have passed on before us.

When Chris died in 2002, I remember waking up that morning and thinking it was a special day somehow, but I didn't remember why, at first. By the time the day was over, and I was making arrangements to travel to Germany, I remembered that it was also Stephen's birthday and I had forgotten. Today the anniversary of those events does not escape my notice. But I didn't set out this morning to grieve, but to celebrate the full life my son Chris had accomplished by the time he had turned forty.

People die prematurely all the time, and in the old days, forty was not so premature. Chris had lots of gray in his hair and although he had not produced any children, it was not for want of trying. I think he really would have been a good father; he was very close to his stepson, Silvia's son from a previous marriage. I am not close to him and only met him during my stay in Bamberg for Chris' memorial service. Silvia is German and her English at the best of times is not good. We are Facebook friends and that is enough for me these days.

Chris worked in the mail room on the Army base and so many people told me of his generous spirit and quick laughter. I remember when he was a young boy that he was fiercely independent. When I would read to him, it was for me and not for him, since he would allow me to read to him but didn't care if I did or not. And forget hugs and kisses! But we would share many things and I remember laughing together at things long forgotten. But I still remember the affection and laughter.

He was a pretty good student. That changed as he grew older and lost interest in academics, but I am grateful that he never experienced the kind of bullying that seems rampant in elementary schools today. Although he was influenced by his peers and took up drugs in high school, it was his habit of smoking that I believe killed him. He tried so many times to quit, and finally managed to give up cigarettes completely a few months before he died. He was so proud of his accomplishment and we emailed back and forth about his struggles and progress.

He had been given a three-month temporary assignment in Macedonia, and he was away from his wife and stepson when he died. His roommate in their quarters told me of Chris' enjoyment of coming into the air-conditioned comfort of his room after a hot day outside, when he would quaff a beer and sit in his skivvies, making everybody laugh at his satisfaction of a job well done, the day's work finished.

Chris would call me twice a year, on his birthday and on Mother's Day. He would tell me of his latest trials and tribulations, but he seemed really happy most of the time, and that was confirmed when I went to Germany. He was not only well liked by his friends and loved by his family, but he loved the Army, and he wanted very much to stay in the service.

I was astounded to learn that he was also known by his friends and acquaintances as a very accurate palm reader and would tell the future that appeared to him in the lines of people's hands. When he developed this interest, I have no idea. But it reminded me that Chris had a second sense about people; he would make instant likes and dislikes to those he met. I had no doubt that he loved humanity and especially his mother. His relationship with his father was a good one, too.

Although I didn't want to talk to Derald (his father) and didn't for years, unless it had something to do with Chris, he kept pushing me to call Derald and talk with him. His desire to have us reconciled was something he never gave up on, and one day, sometime in the 1980s I guess, I called Derald and we talked on the phone for hours. We healed old wounds and spent time forgiving each other for our youthful mistakes. I knew after that phone call that Chris was responsible for removing our old painful memories and replacing them with good ones. Not long after that phone call, Derald died suddenly. He was only 51, and his son Chris would die of the same thing: sudden cardiac death.

Chris has been gone for nine years now, and I didn't see him in person during the last four years of his life, but he lives on in my memories, and I'm sure also in the memories of many others who knew and loved him. The infant I held in my arms almost fifty years ago grew into a very special person who made a difference in the world. Chris, I love you, I will always love you until the day I die.

And then, if there is life after death, we will meet again and I'll join you over a cup of coffee and we'll tell stories of our adventures since we were last together on Earth.

Somebody else made the decision in each case to bury them. I myself will have my body cremated and leave nothing but ashes behind, hopefully to be scattered in some beautiful place. But it won't matter much to me in any event. It's those of us left behind that it matters to. Silvia, Chris' wife, wanted him buried in her cemetery so she could visit him, and that's fine. Everyone has different ways to commemorate those who have passed on before us.

When Chris died in 2002, I remember waking up that morning and thinking it was a special day somehow, but I didn't remember why, at first. By the time the day was over, and I was making arrangements to travel to Germany, I remembered that it was also Stephen's birthday and I had forgotten. Today the anniversary of those events does not escape my notice. But I didn't set out this morning to grieve, but to celebrate the full life my son Chris had accomplished by the time he had turned forty.

People die prematurely all the time, and in the old days, forty was not so premature. Chris had lots of gray in his hair and although he had not produced any children, it was not for want of trying. I think he really would have been a good father; he was very close to his stepson, Silvia's son from a previous marriage. I am not close to him and only met him during my stay in Bamberg for Chris' memorial service. Silvia is German and her English at the best of times is not good. We are Facebook friends and that is enough for me these days.

Chris worked in the mail room on the Army base and so many people told me of his generous spirit and quick laughter. I remember when he was a young boy that he was fiercely independent. When I would read to him, it was for me and not for him, since he would allow me to read to him but didn't care if I did or not. And forget hugs and kisses! But we would share many things and I remember laughing together at things long forgotten. But I still remember the affection and laughter.

He was a pretty good student. That changed as he grew older and lost interest in academics, but I am grateful that he never experienced the kind of bullying that seems rampant in elementary schools today. Although he was influenced by his peers and took up drugs in high school, it was his habit of smoking that I believe killed him. He tried so many times to quit, and finally managed to give up cigarettes completely a few months before he died. He was so proud of his accomplishment and we emailed back and forth about his struggles and progress.

He had been given a three-month temporary assignment in Macedonia, and he was away from his wife and stepson when he died. His roommate in their quarters told me of Chris' enjoyment of coming into the air-conditioned comfort of his room after a hot day outside, when he would quaff a beer and sit in his skivvies, making everybody laugh at his satisfaction of a job well done, the day's work finished.

Chris would call me twice a year, on his birthday and on Mother's Day. He would tell me of his latest trials and tribulations, but he seemed really happy most of the time, and that was confirmed when I went to Germany. He was not only well liked by his friends and loved by his family, but he loved the Army, and he wanted very much to stay in the service.

I was astounded to learn that he was also known by his friends and acquaintances as a very accurate palm reader and would tell the future that appeared to him in the lines of people's hands. When he developed this interest, I have no idea. But it reminded me that Chris had a second sense about people; he would make instant likes and dislikes to those he met. I had no doubt that he loved humanity and especially his mother. His relationship with his father was a good one, too.

Although I didn't want to talk to Derald (his father) and didn't for years, unless it had something to do with Chris, he kept pushing me to call Derald and talk with him. His desire to have us reconciled was something he never gave up on, and one day, sometime in the 1980s I guess, I called Derald and we talked on the phone for hours. We healed old wounds and spent time forgiving each other for our youthful mistakes. I knew after that phone call that Chris was responsible for removing our old painful memories and replacing them with good ones. Not long after that phone call, Derald died suddenly. He was only 51, and his son Chris would die of the same thing: sudden cardiac death.

Chris has been gone for nine years now, and I didn't see him in person during the last four years of his life, but he lives on in my memories, and I'm sure also in the memories of many others who knew and loved him. The infant I held in my arms almost fifty years ago grew into a very special person who made a difference in the world. Chris, I love you, I will always love you until the day I die.

And then, if there is life after death, we will meet again and I'll join you over a cup of coffee and we'll tell stories of our adventures since we were last together on Earth.

Sunday, August 7, 2011

They started it all

Here are my parents, back when they had no children, when they only had each other and their own families, before they made us. My mom had beautiful dark eyes and auburn hair, showing her Spanish heritage, and Daddy's eyes were blue as the sky, with light sandy hair, reflecting his Scotch/Irish ancestry. They had seven children (one died after being born prematurely, Tina Maria), but the six of us who grew to adulthood are all still here. We got together last March in Texas, honoring my brother-in-law Pete, Norma Jean's husband, who died in February. It was a good reunion, although now our extended family is so huge that it was, at times, overwhelming.

All of my siblings have grandchildren, except for my brother Buz, whose daughter Trish is married but not yet a mother. Maybe never, I'm not sure how she feels about it. And my sister Markee's kids are teenagers and not yet married. I am the only one who doesn't have any possibility of grandchildren, but still our family gatherings are enormous. The siblings, which Buz cleverly dubbed the "Sixlings" many years ago, have a few characteristics in common, and I wonder how much they are caused by the genetic makeup that stems from our parents.

Our parents were both above average in intelligence, and all of their children are, too. This is not surprising in itself, but what I really wonder about is our tendency towards attention to detail and perfectionism. Sort of a mild form of OCD, in a way. It's what makes me a good editor; I can't help but see a misspelled word or incorrect punctuation. (It doesn't mean I don't make those mistakes myself, but when I'm working I am quite good at fixing other people's work.) Norma Jean worked at hospitals building databases for medical records; P.J. absolutely LOVES any kind of spreadsheet and can build one in a jiffy. My brother Buz has worked for years as a computer whiz and if I want to know how to do something I will ask him. He will then send me very detailed step-by-step instructions.

The two siblings that I am farthest from in age, Markee and Fia, were both born after I left home and had children of my own. They are very close to each other, but I don't know them very well. Markee is an R.N. and earned several scholarships when she was growing up; and Fia, the youngest, also works for a team of doctors and can help any of us get the medical care we might need. Every single one of us is good at paying attention to detail and every one of us has excelled in his or her job. Most of us never finished college, however. I never had the chance since I started having babies at nineteen, and Norma Jean also married early and dropped out of college. Besides, in the sixties women weren't supposed to go to college unless it was to find a suitable husband. That's what I thought then, anyway.

My own particular symptom is that I count things. I cannot walk up a flight of steps without counting them, usually in sets of fours or eights. I know the number of steps of every place that I go every day, and as I walk up them, counting, it gives me some sort of satisfaction, I can't say exactly what. (The number of steps doesn't vary, but my method of counting them does.) In my exercise class, I always count the number of people in the class at the beginning and notice when someone arrives late or leaves early, adjusting the count in my head. I count the number of people on the bus. I don't know why I do this, but I do.

I don't have any problem with the uncounted jumble of books on my desk or my pencils being misaligned, but I do like straight lines. Sometimes I'll be walking and will make sure that I turn corners precisely, not making short cuts. When I make the bed, I like the lines on the quilt to be in exactly in the same place each time. Now that I'm retired, I seem to be more aware of these things, maybe because I have plenty of time to spend noticing them, or maybe I do it more often.

My siblings all have habits that I recognize as being part of me, too. Did we get this way because our genetic makeup from Mama and Daddy caused it? It's a mystery to me, but it's also quite comforting to think that our parents gave us an invisible thread, joining us to one another, that comes from them and extends on and on through the generations that follow us. It started somewhere way back with our distant ancestors and came to fruition in the unique joining of our mother and father. How cool is that?

I've just barely scratched the surface of this subject, which I'll visit again. It's Sunday morning and I've fulfilled my self-imposed task of writing this post as the sun has arisen and the early morning light spills into the room. I hear the birds now, they are awake on this beautiful August day, and my partner is beginning to stir next to me. My day awaits.

All of my siblings have grandchildren, except for my brother Buz, whose daughter Trish is married but not yet a mother. Maybe never, I'm not sure how she feels about it. And my sister Markee's kids are teenagers and not yet married. I am the only one who doesn't have any possibility of grandchildren, but still our family gatherings are enormous. The siblings, which Buz cleverly dubbed the "Sixlings" many years ago, have a few characteristics in common, and I wonder how much they are caused by the genetic makeup that stems from our parents.

Our parents were both above average in intelligence, and all of their children are, too. This is not surprising in itself, but what I really wonder about is our tendency towards attention to detail and perfectionism. Sort of a mild form of OCD, in a way. It's what makes me a good editor; I can't help but see a misspelled word or incorrect punctuation. (It doesn't mean I don't make those mistakes myself, but when I'm working I am quite good at fixing other people's work.) Norma Jean worked at hospitals building databases for medical records; P.J. absolutely LOVES any kind of spreadsheet and can build one in a jiffy. My brother Buz has worked for years as a computer whiz and if I want to know how to do something I will ask him. He will then send me very detailed step-by-step instructions.

The two siblings that I am farthest from in age, Markee and Fia, were both born after I left home and had children of my own. They are very close to each other, but I don't know them very well. Markee is an R.N. and earned several scholarships when she was growing up; and Fia, the youngest, also works for a team of doctors and can help any of us get the medical care we might need. Every single one of us is good at paying attention to detail and every one of us has excelled in his or her job. Most of us never finished college, however. I never had the chance since I started having babies at nineteen, and Norma Jean also married early and dropped out of college. Besides, in the sixties women weren't supposed to go to college unless it was to find a suitable husband. That's what I thought then, anyway.

My own particular symptom is that I count things. I cannot walk up a flight of steps without counting them, usually in sets of fours or eights. I know the number of steps of every place that I go every day, and as I walk up them, counting, it gives me some sort of satisfaction, I can't say exactly what. (The number of steps doesn't vary, but my method of counting them does.) In my exercise class, I always count the number of people in the class at the beginning and notice when someone arrives late or leaves early, adjusting the count in my head. I count the number of people on the bus. I don't know why I do this, but I do.

I don't have any problem with the uncounted jumble of books on my desk or my pencils being misaligned, but I do like straight lines. Sometimes I'll be walking and will make sure that I turn corners precisely, not making short cuts. When I make the bed, I like the lines on the quilt to be in exactly in the same place each time. Now that I'm retired, I seem to be more aware of these things, maybe because I have plenty of time to spend noticing them, or maybe I do it more often.

My siblings all have habits that I recognize as being part of me, too. Did we get this way because our genetic makeup from Mama and Daddy caused it? It's a mystery to me, but it's also quite comforting to think that our parents gave us an invisible thread, joining us to one another, that comes from them and extends on and on through the generations that follow us. It started somewhere way back with our distant ancestors and came to fruition in the unique joining of our mother and father. How cool is that?

I've just barely scratched the surface of this subject, which I'll visit again. It's Sunday morning and I've fulfilled my self-imposed task of writing this post as the sun has arisen and the early morning light spills into the room. I hear the birds now, they are awake on this beautiful August day, and my partner is beginning to stir next to me. My day awaits.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)