|

| Linda H. Williams on Seeing Bellingham Group |

The festival of Christmas celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ and conveys his message of love, tolerance and brotherhood. It is a celebration of humanity and mankind. Though Christmas is a primary festival of the Christian calendar, it still has a special significance in everyone's life.

When I was a kid, I always hoped to find a special gift for me under the Christmas tree. I knew in my heart that my parents were the ones who found just the right gift (actually, my mother), not Santa Claus. I was never much of a believer, but played along because it was expected. In all the years of my childhood, I must have received hundreds of gifts, but only a few stand out in my memory. When I was around ten, I really wanted a bride doll, and I can still remember seeing it in the store and wanting it so bad. I guess I received it, but it was the wanting that I remember to this day. I suppose I would be wealthy today if I had kept it, pristine and unloved in its original box, but I'll wager that she was loved until she was used up and eventually discarded.

Far more precious treasures were given during those Christmas festivities: family memories, the closeness I shared with Mama and Daddy and Norma Jean, and then eventually the rest of my siblings as they showed up in my life. But especially my sister who was both my playmate and constant companion. As I grew from a toddler to an adult who went off with my first husband, she was always there. We were a very happy family, as I recollect the memories that still emerge when I think of that long-ago time.

The bond that links your true family is not one of blood, but of respect and joy in each other's life. —Richard Bach

What do I remember from my childhood Christmases? There was always a well-decorated tree, covered with lights, ornaments and tinsel. I remember liking to lie down with my head under the tree so that I could look up at the beauty of it, and smell the pine scent, which seemed more intense from underneath. And I was also at eye level with the prettily wrapped presents, even imagining myself being one of them.

As I sit here writing this, in my dark room with my dear partner still sleeping next to me, I think of all the Christmas mornings we have shared together in the three decades we have been together. Since we met as skydivers, we would often spend our Christmas holiday in Arizona jumping out of airplanes. But that was then, and now we are both elders who marvel at what we did when we were young, with no real desire to return to those days. That is actually pretty amazing when you think about how central to our lives that activity was. Today, we will wake up and spend the quiet day together with little to differentiate it from other days.

We no longer exchange gifts; we have no tree standing in the living room surrounded with presents; sometimes we have a lovely salmon dinner, but since the pandemic we haven't even done that. Instead, I will get in John's truck and we'll head off for coffee, much as we do every day, and SG will remain in bed until he's ready to start his day. When I come home, we'll spend some time together, perhaps reminiscing over past Christmases, but in reality just being grateful for our being together during these precious days in the twilight of our lives.

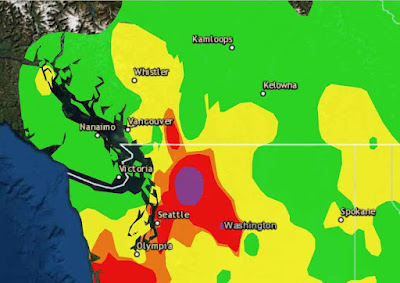

Every year for the past several, I have received a wonderful Jacquie Lawson Advent Calendar from a dear friend as a Christmas gift. Advent is finished today, after a month of wonderful videos and games to play every day, I'll miss it. I just watched the video from the final day that marks the beginning of the Christmas season. I took a picture with my phone to share it with you:

|

| Until next Advent season, Merry Christmas! |

My virtual family, my friends from around the world who visit me on my blogs, whose own blog posts keep me apprised of what is going on in their lives, and those who like to read and don't comment, to all of you I wish you the best of Christmas days on which your future memories will be formed. Until we meet again, dear friends, when we will begin another trip around the sun, I wish you all good things. Be well.